A guest post by Martin Gittins from Kosmograd newsfeed, contributing to the second Ecological Urbanism discussion hosted by Annick Labeca, Taneha Bacchin, DPR-Barcelona and single-blogs.

----

For a while, I was contemplating buying the Last House in London. It appealed to me, the idea of living at the very edge of the city, as far north as it is possible to go, on the outskirts of High Barnet. But on closer inspection it turns out that it isn't the edge of the city at all. Next to the house is a cemetery, then a paddock and stable, and a little further on 2 golf courses. Then there are a couple of fields before you get to a pub, then the estate of Dyrham Park Country Club (one of a string of large country estates encircling London), then a gypsy encampment, the M25 motorway, and the curious environs of South Mimms, a village consumed by a motorway service station.

Image taken from Google Maps / The area to the north of High Barnet appears to be lush, verdant, sward, but on closer inspection reveals a hidden urbanism.

The city has a fractal edge, bleeding urbanity into the countryside, which conversely seeps tendrils of nature into the city. Yet our innate desire to see town and country as two separate realms means that at the edge of cities this landscape becomes a strange hinterland, a secretive fictive space. Development here is almost always ad-hoc, piecemeal, a gradual process of urbanisation - a garden centre or golf course as a vanguard - with the occasional flurry of infrastructural activity, usually a new road, a moment of intensification, seeding new developments.

Interwar planning dogma in the UK threw up the Green Belt (London and Home Counties) Act 1938, designed to stop the untramelled growth of London into the country, to protect against urban sprawl. It arose after vigorous campaigning from the Council for the Preservation of Rural England, and carried with it the overtones of protecting the wealthy country folk, the landed gentry, from the great unwashed lumpenproletariat. (For a town planner Abercrombie was a secret ruralophile). The Green Belt became a politicised landscape, the buffer zone between the haves and have nots. It was a concept that was soon adopted by other metropolitan areas of Britain and then exported to the world.

Image on the left taken from Building Land UK, image on the right taken from treehugger / The Green Belt was exported from London to the rest of the world.

Iain Sinclair, in the wonderful London Orbital, wrote:

"By the time Londoners had seen their city bombed, riverside industries destroyed, they were ready to think of renewal, deportation to the end of the railway line, the jagged beginnings of farmland. Patrick Abercrombie's Greater London Plan 1944 (published in 1945) still worked through concentric bands: the Inner Urban Ring (overworked, fire-damaged), the Suburban Ring (to which inner-city casualties would migrate), the green belt (ten miles beyond the edge of London), and the Outer Country Ring, which would extend to the boundary of the regional plan.

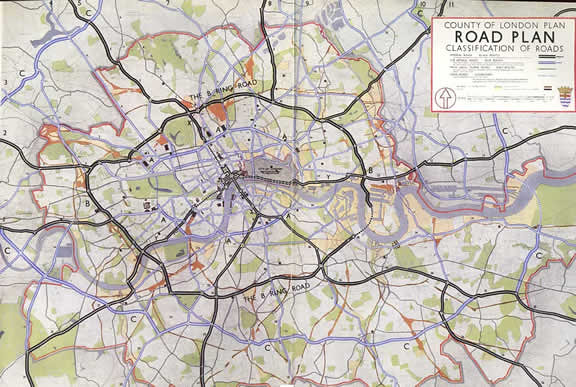

Visionary maps, in muted Ben Nicholson colours, were produced. Lovely fold out abstractions. Proposals in soft grey, pale green, blue-silver river systems. But as always with the blood circuit of ring roads, the pastoral memory ring at the edge of things, at the limits of our toleration of noise and speed and grime. There must, said William Bull (in 1901) be 'a green girdle around London's Sphere ... a circle of green sward and trees which would remain permanently inviolate'".

Image taken from CBRD website / Abercrombie's 1944 Greater London Plan. View larger image HERE.

Post WW2, with London and other urban areas ravaged by bomb damage and with a large displacement of people, a new vision of London arose. It was led by Abercrombie's 1943 County of London Plan, followed in 1944 by the Greater London Plan, and led to the New Towns Act of 1946, with its plan for the extensive enlargement or creation of a ring of towns around London within the Green Belt. Stevenage, Welwyn Garden City and Hatfield were the three designated towns in Hertfordshire.

Image taken from CBRD website / Part of Abercrombie's County Plan of 1943. View larger image HERE.

Image taken from BBC / Welwyn Garden City was founded by Ebenezer Howard but expanded as part of the New Towns Act.

New Towns, heavily inspired by Ebenezer Howard's Garden City Movement, were conceived as places that would not be allowed to grow too big, and maintain a healthy relationship between Town and Country. Certainly Howard thought that Garden Cities could be self-sustaining communities, solipsistic enclaves, with just enough people to support just the right amount of amenities, light industry and offices, enough to provide employment for all the inhabitants. It's a concept that was also mooted for the flawed ecotowns boondoggle of the late 2000s in the UK. But, inevitably, any town is plugged into an infrastructure larger than itself, and so there is a network of transport links, water and sewage systems, power lines and telecoms links that has grown up to meet the needs of these towns.

Image taken from CBRD website / 3 types of arterial road junctions. Abercrombie's Greater London Plan included proposed layouts of road junctions, but gave little thought to what might happen around these junctions, outside of the city.

This infrastructural life support system criss-crosses the green-belt, connecting the towns of Hertfordshire together and plugging them into the beating heart of London. Physically it also carves the landscape into a number of small, leftover spaces. It is into these leftover space that secret urbanism seeps in, the parasitic typologies of golf courses, garden centres, caravan parks, and those other things that spring up along transport interchanges, such as business parks, retail parks, travel hotels, distribution warehouses. The Green Belt seems in places to be little more than one or two fields that keep a satellite town, Bushey, Potters Bar, Broxbourne, from merging into the Great Wen of London.

Image taken from Geograph.org.uk / The Green Belt, as it is today. Retail park, London Colney.

'Abolish the green belt' is an provocative clarion call that periodically raises the hackles of the folks in the Shires, the Home Counties home guard, whether it comes from design figureheads like Kevin McCloud or anti-establishment tyros like James Heartfield. The problem with a Green Belt is that it does nothing to really save the countryside from the encroachment of the city, and instead of presenting sprawl, actually encourages it. But rather than simply abolish it, we need to recognise it for what it has become, and design within it.

The green belt has become not a verdant sward of pastoral beauty but an interzone of pure infrastructure. Instead of resisting the growth of the city, and pretending the resulting drosscape doesn't exist, a new form of continuous urbanism is required, one that can operate at a variety of densities, with points of stim and dross, to use Lars Lerup's terms, more consciously defined.

References

Sinclair, Iain, (2002) "London Orbital", London: Granta Publications

Lerup, Lars (1995) "Stim & Dross: Rethinking the Metropolis." Assemblage 25, Cambridge & London. MIT Press

----

Martin Gittins writes the Kosmograd newsfeed, a blog largely about architecture, disurbanism and urban identity, viewed primarily through the lens of Soviet Constructivism. Trained as an architect, but now working in the field of interactive design, Martin lives in north London with Ms Kosmograd, 3 children and a collection of bicycles. Martin spends most weekends cycling around Hertfordshire considering the 'problem' of London. Martin also writes occasionally at SuperSpatial.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar